How To Fix Your Metabolism After Crash Dieting

We look into how to fix a slow metabolism, discuss metabolic damage and metabolic adaptation, and explore two methods. reverse dieting and all in.

Diet culture is powerful stuff. The allure of a new weight loss diet is so enticing, we often assume that even though the last 10 diets didn't work, this next one will do the trick. Unfortunately, research suggests that for most people, weight loss diets are not sustainable in the long term and often result in us gaining back the weight that was lost – and then some. The reason for this weight cycling (aka weight loss and weight regain) is metabolic adaptation.

What is Metabolic Damage / Metabolic Adaptation?

Metabolic adaptation, better known as metabolic damage or starvation mode, is the body's response to long term caloric restriction or starvation. The term "metabolic damage" tends to make this seem like a really negative unfortunate side effect of caloric restriction or extreme dieting. In fact, metabolic adaptation is a normal and natural survival mechanism. When our body doesn't have enough energy (calories) available to use, it slows down our metabolism to burn fewer calories throughout the day. This is literally a desperate attempt to preserve energy for the body to use for normal every day functions like breathing, digestion, walking, standing, etc.

Major Influencers on Body Weight Changes

Based on what we know about metabolic adaptation and weight cycling, the ability of a person to lose a significant amount of weight for good and keep it off is up for debate. So let's look at this from a calculation perspective and consider what would be required to change your body weight. A lot of people might believe that it's as simple as energy in minus energy out, but it's a lot more nuanced than that.

The ENERGY IN is more realistically:

The actual number of calories consumed

So this information is readily available from food packaging or calorie trackers. However, according to the FDA, the nutrition information on the food label can be off by up to 20% and still be considered compliant. So the calories you see on the nutrition label or the number you're logging into your myFitnessPal may be very different than what you're actually consuming.

MINUS

The calories not absorbed from food

The number of calories in food may not actually equal the number of calories you absorb from that food. Rates of absorption may vary significantly depending on how food is processed, cooked, the fibre content, your microbiome make up etc.

On the other hand, ENERGY OUT is a combination of:

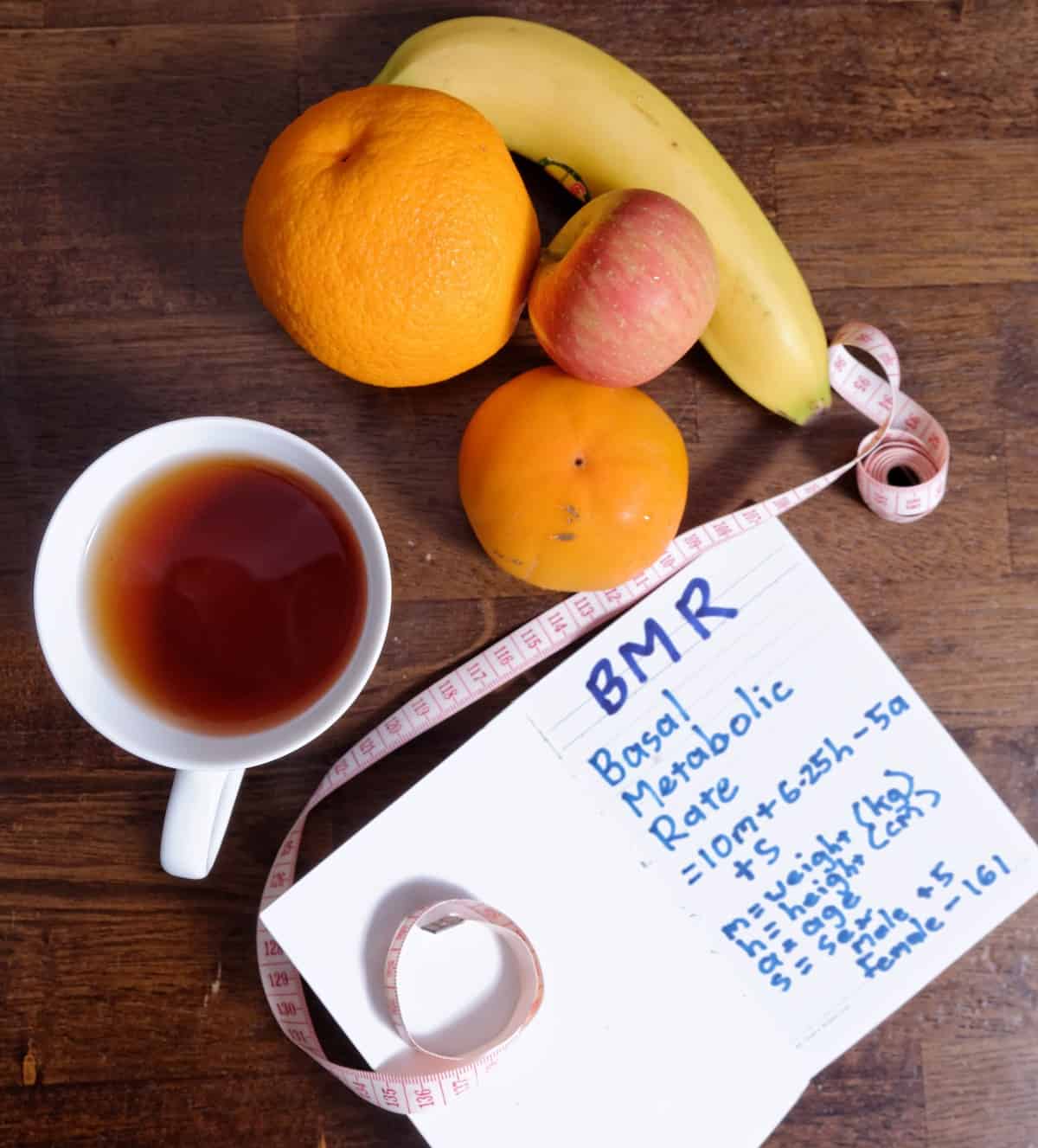

Resting metabolic rate (RMR)

This is the number of calories you burn each day simply at rest. RMR supports bodily functions like breathing, blood circulation, organ function, and brain function and is largely dependent on genetics, age, sex, weight, and possibly gut microflora). RMR represents about 60% (the majority) of our energy output or "metabolism".

The thermic effect of food (TEE)

This is the amount of energy or calories required to eat, digest and absorb food. The amount of energy expenditure varies per macronutrient. For example, carbohydrates and fat require 5-15% of your energy output to digest, while protein requires 20-35%.

Physical Activity (PA)

This is purposeful exercise like going to the gym, jogging, riding your bike etc. The amount of energy expenditure is highly variable depending on an individual's unique activity level.

Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)

These are the little unconscious things you may do that use up energy like fidgeting, sitting up straight, playing a musical instrument, twirling your hair anxiously etc. This makes up about 10-15% of your energy output.

To summarize this information and present it in a simplified math calculation:

Changes in body weight

= ENERGY IN [actual calories in – calories not absorbed] – ENERGY OUT [RMR + TEE + PA + NEAT]

How Does Metabolic Adaptation Happen?

Metabolic adaptation research is largely based on theories like the set point theory and the dual intervention point theory (among other variations on these).

The set point theory suggests that our bodies have a comfortable weight that is genetically predetermined that it will fight to defend. When we decrease our intake and lower our body weight through dieting, for example, we have compensatory mechanisms in place that reduce the energy output and energy input in an effort to maintain homeostasis. Our weight, in this regard, is a lot like a thermostat. If the house gets hot, it's triggered to cool it back down. If the house gets cold, it's triggered to heat it back up.

The Dual Intervention Point Theory considers that we genetically have a set point, but that it's not a static number, but rather, it's more of a range. Outside the upper and lower intervention points, or set point "range", physiological control mechanisms get switched on to bring us back within the range. However, when our weight falls within the set point range, these control mechanisms are weaker. To give you an example, if your set point range is 110-135 lbs, because the physiological control mechanisms for weight are weaker within this range, this range can be more easily influenced and may fluctuate up or down depending on things like diet and movement. However, these efforts are more likely to be thwarted if you try to get outside the range (i.e. down to 100 lbs or up to 160 lb). It's important to note that there is no one range size, and individuals will vary in how "tight" their set point range is. Since everyone's upper and lower intervention boundaries (aka set point range) are different and variable in width, it helps explain why some people's weight seems to be more tightly regulated than others. We all know someone who can eat ANYTHING and stay the same weight, while others have an extra beer on the weekend and gain weight. The former likely has a very narrow set point range, so their body works harder to keep them within that range, while the latter may have a wider range, meaning their weight is more likely to fluctuate to a greater degree.

Based on these theories, when we restrict calories and lose weight below the lower intervention threshold (aka set point range), a few major energy out mechanisms kick in to bring the body back to homeostasis:

- We have less energy available to push ourselves hard in the gym (physical activity declines)

- We may unconsciously fidget or move less (NEAT declines)

- We may absorb more calories from food to compensate for the lack of caloric intake (TEE decreases)

- We weigh less so our body needs fewer calories to sustain that lower weight (RMR decreases).

To summarize, all aspects of the energy out equation (PA, TEE, NEAT, RMR) DECLINE in an effort to balance out the restricted energy in and bring the body back within its normal weight range. Unfortunately, it would appear that this isn't a precise science as metabolism (aka energy out/energy expenditure) may decline more than what you would expect for the change in body weight, likely as a survival mechanism to safeguard against body and fat mass loss. We saw this survival mechanism play out in the popular weight loss reality TV show, the Biggest Loser where results from a 6 year follow up study on 14 contestants from the show showed that not only did contestants regain the weight that they lost, but some contestants gained even more weight than what they weighed prior to participating on the show. One of the most significant findings of this study was the dramatic decline in resting metabolic rate after weight loss. Meaning, they burned fewer calories (about 500 fewer) in energy expenditure than they did before they competed on the show. These results suggest that metabolic adaptations or a slow metabolism is defence mechanism that acts in proportion to weight loss. So for example, if you needed 2000 calories at 150 lbs, and a mathematical equation suggested you would need 1500 calories at 130 lb (after you lose 20 lbs), the sad reality would suggest you would ACTUALLY need only 1000 calories only to maintain your new 130 lbs. Ugh, no wonder people who lose weight gain it back! Note: these are fictitous numbers to make a point.

In addition to changes in metabolic rate, our hormones will likewise adjust to compensate for changes in body weight which can influence the energy in equation. For instance, when we lose weight:

Leptin Declines

Set point theory puts leptin front and centre as the main compensatory player for consumption. Leptin, stored in fat cells, is our satiety hormone and signals to us when we feel full. When we lose weight, these cells shrink and leptin levels drop, meaning our normal healthy fullness signals become silenced. As a result, we feel the need to eat more to feel full as our body fights to regain its preferred weight.

Ghrelin Increases

This is the "hunger hormone" that increases our appetite and tells us when it's time to eat. Ghrelin is inversely related to calorie intake, meaning when we eat fewer calories than what our body needs, this hunger hormone revs up and increases our appetite. Studies show that people who try to lose weight and keep it off end up producing more ghrelin then they did before losing weight, which is the bodies attempt to increase appetite so you eat more and regain the lost fat.

Cortisol Increases

This is the "stress hormone" which is often released under severe caloric restriction or excessive exercise. Increased cortisol can slow metabolism and impair the ability to sustainably lose weight Some studies have even shown that women who consume low calorie diets have higher cortisol levels and report more feelings of stress compared to women who do not restrict their diet.

Increased Insulin Resistance

As we know, insulin is the hormone responsible for regulating our blood sugar levels by assisting the cells in absorbing glucose for energy. Insulin sensitivity, in other words the degree to which the cells respond to insulin and the uptake of glucose, is negatively associated with cortisol. Meaning, when cortisol increases due to severe caloric restriction the cells becomes LESS sensitive to insulin and instead become more insulin resistant and don't respond as efficiently to insulin. This results in higher blood sugar levels, as glucose is not being absorbed by the cells.

All of these compensatory mechanisms become common responses to severe weight loss, caloric restriction and yo-yo dieting as the body fights to maintain its natural "set point" weight or weight range.

Signs and Symptoms of a Slow Metabolism

If you're wondering if you're suffering from metabolic adaptation, some signs to look out for include:

- Gas

- Bloating

- Fatigue

- Heart burn

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Increased hunger

- Sleep disturbances

- Weight gain

- Plateauing

- Anxiety

- Loss of muscle

- Irregularity of periods

- Low immunity.

How to Fix a Slow Metabolism from Dieting

Two of the most common ways to restore a "damaged metabolism" following a period of restriction is reverse dieting and the now popular all-in approach.

What is Reverse Dieting?

Reverse dieting is exactly as it sounds. It's often called the "diet after the diet". It's a way of eating that is usually performed after a diet or a period of restriction. It entails progressively increasing calories over a certain period of time to boost up resting metabolic rate (RMR) back to its "original" (or close to its original) rate.

How to Reverse Diet to Fix Metabolism

The truth is, there isn't a lot of peer reviewed research on reverse dieting. This is a method that has largely been used in the fitness competition and sports nutrition arena, and success is largely anecdotal. In lieu of adequate scientific research, I spoke with two sports registered dietitians who frequently use the technique to get their thoughts.

Sports dietitian, Chelsea Cross of MC Dietetics suggested that caloric restriction can often cause the body's metabolic rate to adjust to a slower rate, and that slowly increasing calories through reverse dieting is an attempt to increase the metabolic rate back to baseline. Sports dietitian and founder of Evolved Sport and Nutrition, Ben Sit, also stated that it's natural and normal for the body to adjust its metabolic rate to preserve calories for energy throughout the day.

Under the care of a sports dietitian, a client attempting reverse dieting would increase their calories by about 50-100 per week while adjusting for this amount if weight or fat gain was occurring too quickly. They would do this until a particular weight goal, caloric goal, or perceived set point was reached. There can be a lot of experimentation involved, but because the progression is so slow and calculated there is a lower risk of "overshooting" the desired or set point weight (by very little, at least).

As with any diet that involves adding calories after a period of restriction, Sit explained that it's important to monitor for the "signs and symptoms of refeeding", referring to the clinical condition called refeeding syndrome. Refeeding syndrome occurs when someone with a low body weight consuming a low-calorie diet over a sustained period of time drastically increases their calories. This causes a potentially fatal shift in fluid and electrolyte balance due to a spike in insulin in response to greater caloric intake. This is often a major concern in eating disorder recovery, but it can also occur after prolonged dieting or restrictive eating. Both dietitians agreed that a caloric increase of 50-100 calories per week is generally safe to prevent refeeding syndrome and not likely to result in extreme fat or weight gain. However, some people can tolerate greater amount of calories outside of this range while others need to be more conservative. This is why it's very important to work with a professional on your reverse dieting journey.

"All In"

The all-in approach is a process created by Dr. Nicola Rinaldi which was informed by previous treatment methods used in eating disorders recovery. It was originally developed to restore hormonal function quickly in order to reverse symptoms of hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA) such as menstrual irregularity, extreme hunger, lack of libido, infertility, and temperature sensitivity. While Rinaldi didn't develop the concept for metabolic recovery, per se, the all-in approach is now often used to restore metabolic function, albeit faster than reverse dieting. One study looked at the resting metabolism of women who had HA, and then again when they recovered from their HA and their hormones returned to normal. The difference was an impressive 300 calories a day!

How to go "All In"

In Dr. Rinaldi's book, "No Period, Now What?", she suggests that recovery involves three main pillars which she encourages people to stick to for a minimum of 6 months to see a complete recovery. The requirements include:

- Following her eating plan daily (aiming for a minimum of 2500 kcal/day without a maximum, allowing yourself to eat to full satiety).

- Cutting out all high intensity exercise.

- Reducing stress and making time to relax.

It's not uncommon for people who have come off of a period of intense restriction to experience "extreme hunger" and therefore need a lot of calories. This is your body's way of begging for, not only enough calories to return to baseline, but also to help replenish your body after months or years of underfueling it.

Since the body is operating at a lower metabolic rate while consuming a suboptimal amount of calories, once you jump up to the 2500 calorie minimum, it's expected that you will gain weight and fat. This is normal. In fact, Rinaldi suggests that most studies and surveys found that the weight gain tended to bring people into a BMI of 22 or more, which is what she calls the "fertile zone". Everyone's fertile weight is different, and it may be higher than the weight you aesthetically think you should be. The weight gain therefore may be a little, or it may be a lot.

You may also gain what is often termed "overshoot weight". This is a term that Rinaldi herself really dislikes (and for good reason considering a moral weight stigma inherently attached to it). Essentially, some people who follow the "All In" approach find that they may initially gain "extra" weight, but as their metabolism adjusts, this weight resettles down slightly and plateaus. While this does not happen to everyone, and a lot of people may simply plateau at a higher weight when they reach their true set point, if it does occur, it may be for a few different reasons. One is that the initial weight gain may cause changes in fluid and electrolyte storage which can cause water retention and bloating. Two, is that some people (particularly those who come from a disordered eating history) may have very high caloric needs when they begin "All In" as they not only need calories for baseline needs, but also for repairing and refueling damaged metabolic systems. Over time, once the repairing is complete, these caloric needs may drop and regulate to just cover baseline needs. And three, at the beginning of the "All In" journey, one's metabolism will likely be pretty slow, which can result in a quick (sometimes significant) jump on the scale. But once metabolism catches up and adjusts to the new incoming caloric load, it's possible we would see the weight come down and stabilize.

Rinaldi did warn that she strongly dislikes even discussing overshoot weight since it gives the impression that it's only okay to gain the weight because you'll lose a lot of it once things stabilize. When in fact, gaining weight, even if it is a lot of weight, and not losing a single pound may be necessary for maintaining health.

Benefits and Disadvantages of Reverse Dieting vs All In

Evidence on reverse dieting and its alleged benefits is lacking, but experts who use this strategy with their clients find that the slow stepwise method to increasing caloric intake allows for gradual metabolic adaptation and reduces the risk of gaining excess fat and weight, while preserving lean muscle mass. This is largely based on anecdotal clinical evidence and not from scientific trials.

The downside is that reverse dieting, like any dieting, may not be appropriate for those struggling with disordered eating, which is actually not uncommon for individuals coming from an extreme diet or pattern of restriction. Carefully counting calories with the goal of metabolic restoration with minimal weight gain can further perpetuate disordered eating and will not help an individual ease back into a more flexible healthy relationship with food and their body. There is also a concern that because the goal of reverse dieting is to slowly bump up caloric intake without risking weight or fat gain, an individual may never reach their body's true set point weight. And instead, they may continue to be fueling their body at a suboptimal level for their unique needs but stopping when their goal weight or desired weight is threatened by a further caloric increase.

The other concern is that reverse dieting does not achieve metabolic restoration quickly, so for those who are suffering with the physiological health implications of metabolic damage (like hypothalamic amenorrhea, infertility, thyroid disfunction and other hormonal irregularities), they may not achieve the timely recovery they really need.

In contrast, the "All In" approach is arguably the most efficient way to restore hormonal regulation (and by default, metabolism) following a period of restriction. This will mean improvements in everything from sleep, menstrual cycle, thyroid, hunger and fullness cues etc. It is also a more intuitive approach that can help you reach your body's natural set point while re-learning (often for the first time in a long time) how to listen to your body's true hunger and fullness cues.

In my professional opinion, I consider the "All In" approach to be true recovery from restriction. While Reverse Dieting can offer some significant health benefits, it may not allow for full healing to occur – both psychologically and, in some cases, physically. In other words, "All In" is exactly what it sounds like when it comes to refueling your body, while Reverse Dieting may not be going ALL the way but some of the way at a much slower pace. It could get you all the way, but it also could not.

When to go All In vs Reverse Diet

It really depends on the goals and the health concerns of the individual. A faster reverse diet or an "All In" approach may be beneficial for someone having complications with their health (ie. Infertility, amenorrhea, extreme hunger etc.) due to a low caloric intake or body fat level.

In contrast, a slow meticulous reverse diet may be beneficial for those who want to increase their caloric intake while minimizing fat gain and maintaining muscle mass as best as they can.

I would argue that a reverse diet may not be suitable for anyone with a past or present history of disordered eating who should be focusing on regaining body trust, not on another weight-driven diet (even one that involves ADDING calories to the diet).

Some people may choose an "All In" approach if they are looking to balance and restore their hormones, metabolism and general health at a faster rate, while also working on their relationship with food and their body.

Whichever you choose, Ben Sit warns that people who have been doing "keto, prolonged starvation, or other extremely low-calorie diets" need to make sure that they are being followed by a professional when attempting any kind of extreme rehabilitation diet as they may not recognize the potentially fatal side effects of refeeding syndrome.

Other Steps for Fixing Metabolic Damage

Other than increasing caloric intake (either quickly or at a slower step wise pace), there are a few additional ways to attempt to improve metabolic adaptation.

Reducing Intense Exercise.

We know that exercise is really important but it can become problematic when its excessive, not supported by adequate caloric intake, or affecting you mentally. Intense exercise will not only burn the calories that you're carefully trying to add during metabolic restoration, but it can also increase stress hormones like cortisol. High cortisol levels have been shown to increase insulin and blood glucose levels, which in turn have been linked to an increased risk of obesity and slowed metabolism. Pull back on any long or intense cardio sessions, and stick to gentle strength training, yoga, stretching, and easy walks instead.

Getting More Sleep.

Sleep allows our body to repair itself physically and mentally. Research suggests that when sleep is restricted, cortisol levels rise, which does tend to play a role in metabolism and weight gain over time. Skimping on sleep also seems to further reduce leptin and increase ghrelin, two hormones that are already impacted by metabolic damage.

Reducing Stress.

Stress can of course be in the form of exercise or lack of sleep, but it can also emerge from other life experiences and factors as well, all of which can increase cortisol levels. Look for ways to reduce the stress in your life by engaging in relaxing activities like meditation, journaling, talk therapy, yoga or other acts of self-care.

Bottom Line on Reversing Metabolic Adaptation

The truth is, if you want to improve your metabolism and fix metabolic damage after a period of severe caloric restriction, there are two popular methods to do so. One is a more calculated, but arguably less "effective" method at achieving full metabolic remission – Reverse Dieting. While the other, is more aggressive, but faster and more thorough – the "All In" Approach. Gaining weight and body fat may be part of the process regardless of which method you choose, and it may in fact be necessary for overall health.

Whichever method you choose to reverse metabolic adaptation, it's very important that you work with a registered dietitian, and if you're coming from an eating disorder history, a full medical team, to ensure you're not at risk of refeeding syndrome.

Now I would love to know – what are your thoughts on metabolic adaptation after dieting? Have you found your metabolism is lower the more diets you have attempted or the more weight you've lost? Leave me a comment below with your thoughts!

Edited by: Giselle Segovia RD MHSc

How To Fix Your Metabolism After Crash Dieting

Source: https://www.abbeyskitchen.com/how-to-fix-a-slow-metabolism-reverse-dieting/

Posted by: pickneywastione.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Fix Your Metabolism After Crash Dieting"

Post a Comment